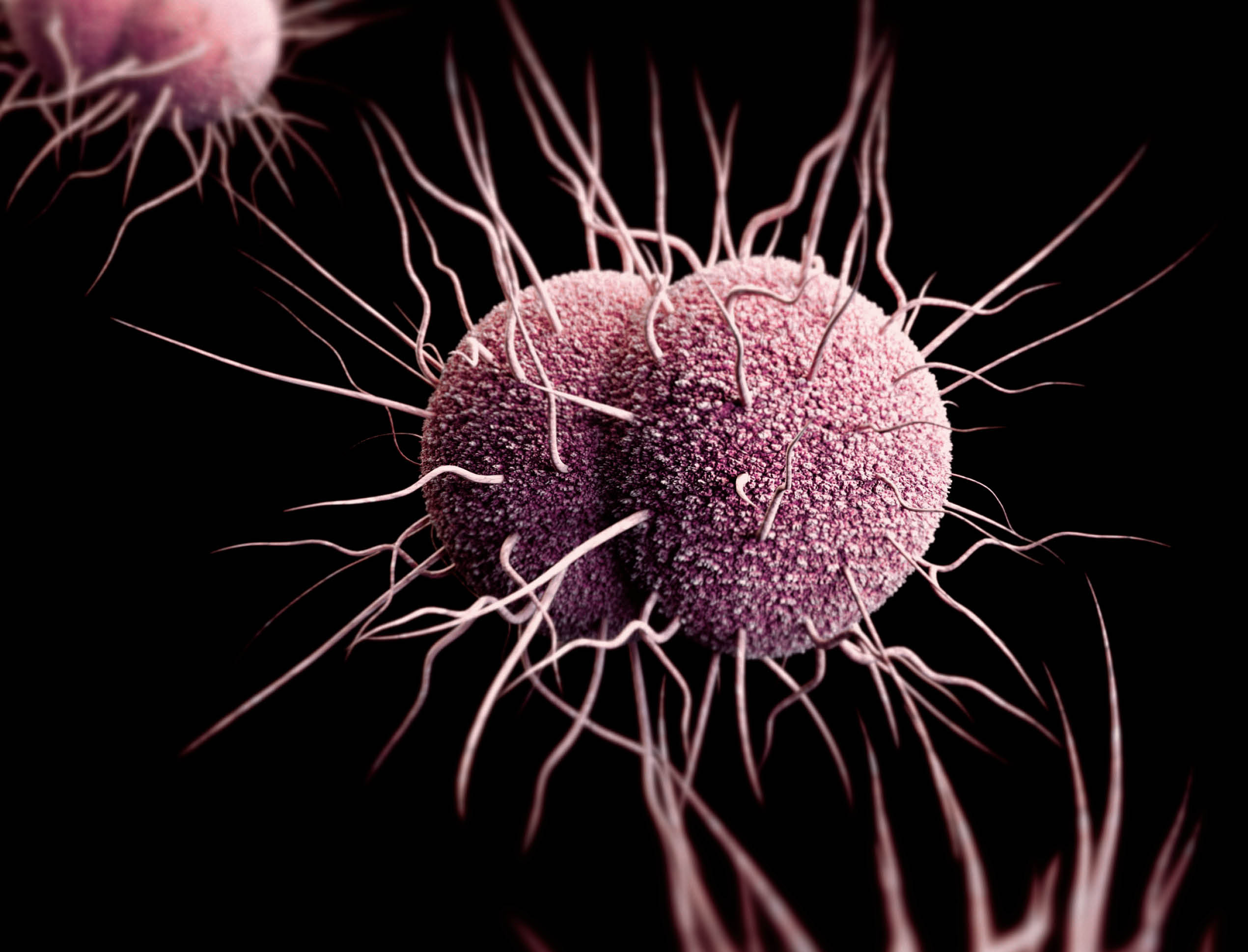

The NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has awarded UNC’s Marcia Hobbs and Alex Duncan a five-year, $3.9 million grant to study how a vaccine recently developed to prevent life-threatening infections caused by group B Neisseria meningitidis, the MenB vaccine, may also protect people from infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a sexually transmitted bacterial infection.

“The notion that the two, meningitis and gonorrhea, are connected sounds crazy at first, but based on the underlying microbiology, the pathogens are actually very closely related,” says Hobbs, PhD, professor of medicine and microbiology and immunology.

Although N. gonorrhoeae has been recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and the World Health Organization as a major public health threat due to rising resistance to antibiotics in the bacteria around the world, the development of a gonococcal vaccine has been stymied for decades. N. gonorrhoeae is one of a number of pathogens that exists only in people, so the only way to study it and test treatments and vaccines is by conducting human studies. Normally, vaccine prevention trials require thousands of participants to test their effectiveness against naturally acquired infection, but Hobbs and Duncan’s trial can test the effectiveness of a vaccine against gonorrhea with less than 200 participants by relying on a study design known as a controlled human infection model, or CHIM. Such trials operate under strict ethical standards, with participants volunteering to be infected with the bacteria under controlled conditions.

“UNC has been running this CHIM for decades,” says Duncan, MD, PhD, an infectious diseases physician and professor of medicine and pharmacology. “The program was pioneered by Janne Cannon, a microbiologist, and Mike Cohen and Fred Sparling, ID physicians.” In the 1990s, UNC was one of two centers leading research in N. gonorrhoeae using this model. Marcia and I continued to use the model, and now we are the only ones in the world doing it.” Similar to the partnership of Cannon, Cohen, and Sparling three decades ago, Hobbs and Duncan bring complementary skill sets in microbiology, immunology, and clinical infectious diseases, making them an ideal team to lead this project.

Developing vaccines for three sexually transmitted diseases — gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis – is a major research focus for the National Institutes of Health because of surging cases of the three diseases in recent years. “One of the primary impediments to finding vaccines to prevent these infections is the fact that we don’t understand the types of immune responses that actually prevent these infections,” Hobbs says. “Humans generally fail to develop immunity after being naturally infected.”

Working with collaborators Andrew Macintyre at Duke and Alison Criss at the University of Virginia, Duncan and Hobbs plan to study the immune responses to the vaccine and the relationship of those responses to protection against the challenge infection.

“We expect that the vaccine will only provide partial protection,” says Duncan. “Because the vaccine was developed to fight the related meningitis bacteria, it won’t be 95 percent effective in preventing gonorrhea. But if we see protection in 25 or 30 percent of our participants, we can learn about the immune responses that are responsible for protection. Our results can feed forward into basic vaccine development to learn how to make a better vaccine to prevent N. gonorrhoeae infection. It will be a home run if we get to the point where we can say, this MenB vaccine protects some people, but now we know what kind of immune response is needed to make a highly effective gonorrhea vaccine.”