The NIH has awarded a multi-disciplinary team led by Ross Boyce, MD, MSc, a $4.4 million, five-year (R01) grant to evaluate the effectiveness of a chemoprevention effort designed to prevent malaria outbreaks after flooding, using a combination of interventions. Boyce is a member of the Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases (IGHID), an Assistant Professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases and Faculty Fellow in the Carolina Population Center.

The project builds on findings from a “proof-of-concept” pilot study, one aspect of which was recently published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases. In addition to collaborators from the Mbarara University of Science and Technology in Uganda, key investigators include Jonathan Juliano, MD, MSPH, also from IGHID; Raquel Reyes, MD, MPA, Division of Hospital Medicine; Elizabeth Frankenberg, PhD, Department of Sociology; Sean Sylvia, PhD, Department of Health Policy and Management; Bonnie Shook-Sa, DrPH, Department of Biostatistics; and, Michael Reiskind, PhD, NC State Department of Entomology.

Disease outbreaks and climate-related health emergencies have reportedly reached their highest levels ever in the greater Horn of African, and this includes western Uganda where an increase in the frequency of extreme precipitation events, likely exacerbated by changes in land use, is believed to have resulted in seasonal surges of malaria transmission. Children under five years of age are particularly vulnerable, accounting for an estimated 70% of all malaria deaths.

First: ‘Proof of Concept’ Pilot Study

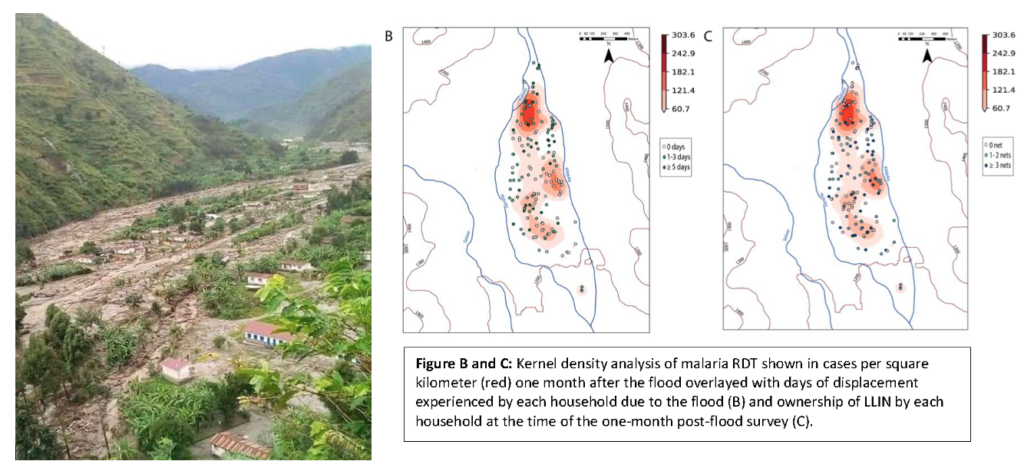

In May 2020, researchers piloted a malaria chemoprevention intervention—namely providing children under 12 years of age with a monthly medication to prevent malaria—in the Izinga Village at the foothills of the Rwenzori Mountains, bordered by two rivers. When the rivers began to overflow after a 30-day period of daily rainfall, over 100,000 residents in the larger region were displaced. In addition to estimating the effectiveness of chemoprevention, the team performed a prospective analysis of the spatial factors influencing household malaria risk, at multiple time points after flooding, using geographical information systems (GIS). Recently published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, the “proof of concept” study recognizes the spatial and temporal distribution of the vector-borne disease, including “hotspots” and target areas for interventions amidst a rapidly evolving environment.

Dr. Boyce says the research, when combined with rapid household surveys, can be utilized to guide an ongoing humanitarian response, highlighting areas that may require additional interventions to control malaria outbreaks as conditions evolve. He also adds that local adaptation and mitigation strategies that may include infrastructure improvements to better manage floodwaters and relocating residents from the highest risk areas, are essential to preventing excess morbidity and mortality.

“In many ways, these are the same types of issues facing coastal areas of North Carolina that are increasingly affected by hurricanes and sea rise,” said Dr. Boyce. “The impact of global climate change, including the increased frequency of weather extremes such as flooding, on the incidence of malaria and other vector-borne diseases, is an issue of great public health importance. While the long-term solution is involves reducing global carbon emissions, it’s imperative that we develop interventions to mitigate morbidity and mortality in the near term.”

Next: Evaluating a Combination Of Interventions

The new NIH R01 award will enable Dr. Boyce and collaborators to build upon this work, with a targeted, time-limited malaria chemoprevention intervention, with and without targeted management of mosquito breeding sites, to reduce excess malaria burden. The project is a cluster-randomized trial conducted in 50 flood-affected villages of rural western Uganda, to determine the effectiveness of chemoprevention with or without larvicide application compared to bed net distribution, which is currently the standard of care. Malaria chemoprevention is the administration of antimalarials to children at the highest risk of malaria at specific ages throughout the year. The intervention provides protection from malaria disease while allowing for some acquisition of natural immunity.

Researchers will also perform weekly surveillance for adult and juvenile Anopheles mosquitoes in select households. These will be tested for the presence of malaria parasites, to understand the evolution of vector populations, mosquito feeding behaviors, and infection rates up to one year after flooding. In addition, researchers will conduct baseline and longitudinal quantitative surveys in sample clusters, to evaluate impacts of the interventions on economic activities and income, health seeking and expenditures, and mental health and wellbeing.

Logistically, studying the health impacts of extreme climate can be very challenging as events are unpredictable. However, severe flooding has become increasingly predictable in western Uganda, which, Boyce says makes the site ideally suited for this type of research.

“I greatly appreciate the willingness of the NIH to invest in this type of work, which involves some degree of uncertainty and a higher tolerance for risk than research conducted in the laboratory or more established clinical sites. I’m optimistic that we can successfully demonstrate how to mitigate the risk of malaria and other vector-borne diseases in a rapidly changing climate.”

UNC’s Uganda partnership, led by Ross Boyce, MD, MSc, and Raquel Reyes, MD, MPA, researchers at the Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases, with P-Healed and the Mbarara University of Science and Technology, has a number of ongoing malaria studies targeting the most vulnerable populations in western Uganda.

The UNC Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases (IGHID) is an engine for global health research and pan-university collaboration, transforming health in North Carolina and around the world. IGHID facilitates research excellence while providing opportunities for investigators to nurture emerging scientists through training and service, to advance patient care and practice.