Dr. Billy Fischer talks about his experiences with Ebola and other viral hemorrhagic fevers in an interview with Lauren Sauer, MSc, director of the special pathogens research network at NETEC and associate professor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC), and Rachel Lookadoo, a public health lawyer and assistant professor at UNMC. Dr. Fischer is a pulmonary critical care physician who directs emerging pathogens efforts through the Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases at the UNC School of Medicine. Led by Fischer and Dr. David Wohl, UNC was recently selected to become a Regional Emerging Special Pathogen Treatment Center.

Fictional scenarios of disease outbreaks and their horrors bring big screen thrills. They can also inaccurately shape public perceptions of real-life microbes. In a new podcast published by the National Emerging Special Pathogens Training and Education Center (NETEC), Billy Fischer, MD, explains what is science and what is Hollywood in favorite shows and movies like Jack Ryan and the Hot Zone. Following is part one of the edited transcript from the podcast.

Q: Tell us about your background with pathogens and viral hemorrhagic fevers.

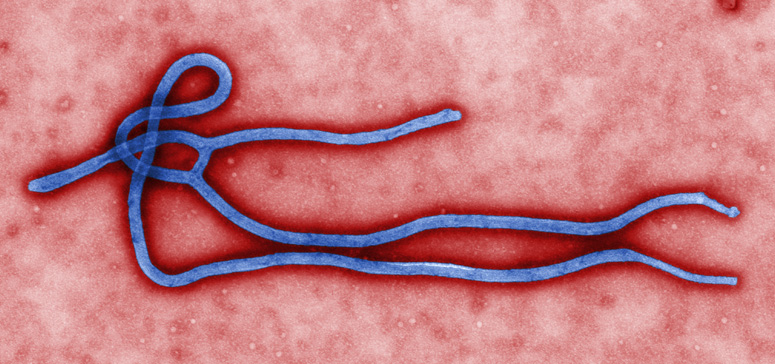

“I am a pulmonary and critical care physician and clinical research at the University of North Carolina. I’ve been deployed to outbreaks of Ebola Virus Disease in Guinea, Liberia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sudan Virus disease in Uganda, Lassa Fever in Liberia, and COVID-19 in South Korea and Azerbaijan. Most of my experience comes from the bedside, providing direct patient care and introducing new therapeutics, but also from the research side trying to better understand the clinical course of these diseases and the pathogenesis of these emerging viruses. I co-lead an intensive research portfolio, along with Dr. David Wohl, to better understand long-term complications of Ebola Virus Disease in survivors, as well as the prevalence and pathogenesis, and even the persistence of Lassa virus in patients with Lassa Fever. ‘Viral hemorrhagic fevers’ is a catch all term to describe a group of diseases that have been associated in some sense with bleeding in patients. It’s really an important misnomer because the vast majority of people don’t have the kind of bleeding that is life threatening. I actually don’t like the use of this term to describe what is really a diverse group of viruses and diseases, but that’s how it’s been used in the past.”

Q: When you see these patients, how do they compare to their portrayal in popular culture?

“This is an important question that links back to the role of popular media in in describing diseases like Ebola virus disease or Lassa fever. The first time I was sent into an outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease, I had this preconceived notion, based on what was described in popular media books and movies, of patients literally bleeding from every orifice, and it was terrifying. Right before I got on the plane, I gave my wedding ring to my father because it was my granddad’s, and we wanted to make sure it stayed in the family. The reason I tell this story is because it highlights how scared I was of Ebola, and how little I actually knew about it. And I can tell you it was terrifying. The worst part was getting on the plane and every moment up until I actually stepped into the Ebola treatment unit. It was only once I stepped into the Ebola treatment unit that I realized that everything I thought I knew about these viruses was absolutely wrong because the patients looked exactly like the patients that we took care of in Baltimore, or in Chapel Hill. They were really sick people.”

Q: One of the things about these shows is the fear factor. In season one of Jack Ryan, a body is dug up in Liberia that was known to have been infected with Ebola, to make a bio weapon out of it. In the Hot Zone, there’s a long discussion about an Ebola outbreak that happened several decades ago in Reston, Virginia. While it didn’t infect humans, there was a huge scare around that outbreak that we now call Ebola Reston because of the chimpanzees that were being infected. How well do each of these stories get it right about Ebola?

“In general, both get it pretty wrong, and I think there are important consequences for getting it wrong. The dramatized description of patients invokes incredible fear which prevents healthcare workers like us from going over to outbreaks and providing care to people who need it. It also creates this mythology around the virus that in some ways has sustained really high mortality rates. Fear of the virus has allowed us to create a barrier around those who are infected and that barrier has prevented the kind of care that is needed to save their life – the kind of care that you and I provide every day to patients in Baltimore or Chapel Hill. It’s taken us decades to break through that mythology and reduce that mortality rate. In the Hot Zone, there are a couple of individuals that are described with Ebola virus disease – there’s a man in a waiting room in a hospital, and he’s vomiting blood everywhere, and they talk about the liquification of his organs–all of which is completely fictional. The book focuses in on an extreme version of the disease that is extraordinarily rare and from limited autopsy reports, there is no mention of liquefying organs. Vomiting of blood can happen, but it typically happens in more severe cases and the amount of blood that is lost is rarely ever sufficient to actually be the cause of death. Most of these patients die from multi-organ failure, the same is true for many patients who die from sepsis. I think the story has an important role in introducing people to this family of viruses, but it does so in a way that evokes a fear that prevents us from responding effectively. For instance, we’ll hear about an Ebola virus outbreak in a particular country and then restrict flights from that country because we’re scared of it spreading to the US. I would argue that is exactly the wrong response, because it will sustain ongoing transmission and increase mortality within that affected area, which ultimately increases the chances of transmission not just within that country, but also outside the country. We have to respond, not with fear or stigma, but by stopping the outbreak out at the source.

“In the Jack Ryan show there is this idea of digging up bodies and developing a bio weapon. The involvement with dead bodies is important to discuss because this virus is transmitted through direct contact with an individual who is infected with Ebola virus, or direct contact with their body fluids, or direct contact with a dead body from Ebola virus disease. With Ebola, unlike SARS-CoV-2 the virus that causes COVID-19, the level of virus increases as people get sicker, and some of the highest levels of virus that we see are in dead bodies. The preparation of a body for burial is something that is sacred and cherished, a custom that is highly important in many societies. But with Ebola, it can be incredibly dangerous because of the high risk of transmission. This is a high-risk event so we have to preserve this cultural practice in a way that also maintains infection control. For example, in one outbreak, I saw a patient who died from Ebola virus disease and was buried, but not according to the customs of his faith. Close members of his friends and family dug up his body and buried him in a way that was culturally appropriate. Customs are really important and valued, but it was conducted in a way that led to transmission to eight of the people that participated in this burial process. And all of them died.”

Q: In the show, Ebola was portrayed as something that could be obtained from digging up bodies and put into an ingestible form, like a vitamin or a pill or something like that. Is that a reasonable way of transmitting Ebola?

“Ebola virus is transmitted through direct contact with an infected patient or their body fluids and the mucous membranes or cuts in the skin of an uninfected individual. The mouth is potentially one portal of entry into your body. While the natural reservoir of Ebola virus is not definitively known, it is believed to be a bat and the preparation of bat meat or the meat of an infected animal is another potential mode of transmission. Another means of transmission is via sexual contact as well. We’re learning that in people who survive Ebola, there can be a persistence of the virus in immune privilege sites, including the testes, and that can lead to potential sexual transmission, but we have more questions than answers about the persistence of virus and we’ve already started evaluating therapeutics to reduce persistence in genital fluids.

Q: In 2014, there were some researchers suggesting that Ebola had the potential to become airborne. Is that a feasible route of transmission?

“Airborne transmission does not look like a mode of transmission that is commonly seen in outbreaks. In fact, there are really good epidemiologic studies of households where a family member or household member was infected, and the other people in the home who got infected were those who had direct contact with the initial infected person. But people who were living in the same households, who did not have direct contact with the infected person, did not become infected, highlighting the role of direct contact in transmission of Ebola virus. So, I think there’s strong evidence that aerosol transmission is not a likely route of transmission. Now, people often counter that argument by saying, we can infect animals by artificially aerosolizing a virus. And that is true, there have been studies that have led to the infection of nonhuman primates and mice, via aerosolization of the virus. So, there is the potential to artificially create aerosols that lead to infection, but that this is not something that is seen in natural disease. This is an important consideration as care is advanced for patients with EVD including the use of aerosol generating procedures and as the care settings change which could affect ventilation.”

Q: In the Hot Zone television series, based on the book, positive pressure suits are used. Can you talk a little about the distinction of that PPE, or what you would use in an Ebola treatment center, versus the PPE you would use in a clinic?

“Positive pressure suits which are used in some of the biosafety level four laboratories in the US and Europe, provide positive pressure to the suit so that if there are any holes in the suit, air rushes out, as opposed to air rushing in, and this theoretically keeps a person safe. As you can imagine, it’s incredibly difficult to work in that environment. We have no positive pressure systems in the field because you have to make an Ebola treatment unit pretty quickly in these outbreak settings in order to isolate and provide really effective care to patients, and this doesn’t often have a lot of the infrastructure needed for positive pressure suits. But we are well protected. In 2013, we were using suits that were made of tychem, which is this incredibly impermeable material, and it’s essentially like being in a Ziploc bag. The suit covers every part of your body, except for your head, and then you have a hood that goes over your head. You wear an N95 respirator underneath that hood and then goggles over your hood. So, you’re completely sealed. No part of your skin is exposed to air. The downside of this, of course, is that it’s really hard to do your job in this Ziploc bag. I once took a laboratory thermometer in my pocket, and the temperature inside my suit reached over 115 degrees. So, it really limits the time that you can spend in that Ebola treatment unit and as a result the care afforded to patients is also incredibly and detrimentally limited as well. Since then, we have used suits made of different materials, including tyvek, which is a little bit more breathable, but still, it makes for very difficult conditions to work.

“At the same time, important structural changes to the Ebola treatment units have allowed better access between patient and provider. One example is something called the CUBE, developed by an NGO called ALIMA. It has a system where you can literally step into the cube without any PPE on and evaluate the patient, perform ultrasound on the patient, observe the patients provide medications, without PPE, that obviously allows you to monitor patients more closely and for longer duration. So the change in the treatment unit enables better access between patient and provider and as a result better care.”

In Part 2 of this interview coming soon, Dr. Fischer talks about caring for patients with Ebola. He also addresses the increase in outbreaks and how climate change contributes, while recognizing the need to break down the facade of fear. The full podcast can be accessed here.

The National Emerging Special Pathogens Training and Education Center (NETEC) strives to set the gold standard for special pathogens preparedness and response across health systems in the United States. With the goal of driving best practices, closing knowledge gaps and developing innovative resources, NETEC works alongside and in cooperation with the CDC and is funded by ASPR, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR).

The ASPR recently selected UNC to be a Regional Emerging Special Pathogen Treatment Center (RESPTC). This means UNC will become a regional expert in civilian biodefense, joining Emory University, as the only two RESPTCs in the Southeast. William (Billy) Fischer, II, MD, and David Wohl, MD, along with UNC colleagues, will lead the new Center funded through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR). Read more.

The Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases at the UNC School of Medicine in Chapel Hill is a research engine for global health innovation and pan-university collaboration, transforming health in North Carolina and around the world through research, training and service. We are passionate about research excellence and training that nurtures emerging scientists, physicians and public health practitioners, striving for the highest attainable outcomes in patient care.