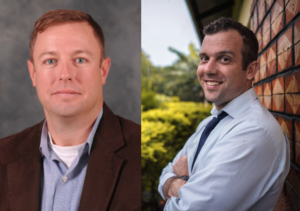

Ross Boyce MD, MSc, partners with Western Carolina University and Mission Hospital to lay the foundation for effective patient care, prevention and public health awareness–funded by the State of North Carolina through the N.C. Collaboratory.

In September of 2022, a 10-year-old in Brevard, North Carolina, complained of intense headaches, chills, fever, and extreme fatigue. Her mother Bailey Kavanagh thought it was probably something her daughter picked up at school. Three days later when nothing was working for the pain, the child was treated for Strep A at the local emergency room. But Kavanagh knew something wasn’t right when her daughter started vomiting. She turned to her pediatrician for answers, who reviewed test results and wrote on paper, instead of speaking out loud, she’s “probably going to Mission.” Kavanagh knew the situation must be serious to be transferred to Mission Hospital in Asheville, an hour away. In an October 2022 podcast chronicling her daughter’s frightening illness, she revealed that the “unofficial” diagnosis was La Crosse Encephalitis, a relatively uncommon disease that can cause brain swelling as well as long-term neurological disability, caused by the bite of an infected mosquito.

Ross Boyce, MD, MSc, a researcher with the Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases at the UNC School of Medicine, studies La Crosse and other vector-borne diseases, including malaria in the highlands of western Uganda. He says when it comes to prevention and control, malaria and La Crosse have a lot in common. In rural Uganda, where transportation options are limited, getting patients to the clinic is the hardest part. Once there, effective diagnostics and treatment are available. That’s not the case for La Crosse.

“There is no vaccine, no good diagnostic testing options, and no anti-viral treatment for La Crosse. So, I would consider it in the realm of neglected tropical diseases, where Western North Carolina, along with Ohio, probably bears the highest burden of virus,” Boyce said.

An Emerging and Persistent Threat to North Carolina

La Crosse is usually acquired through the bite of the Eastern treehole mosquito (Aedes triseriatus). It was first identified in 1960, in La Crosse, Wisconsin, but Boyce says the highest concentrations of the disease today are seen in Western North Carolina, Eastern Tennessee, West Virginia, and Ohio, with the bulk of the disease occurring in the Appalachian range where dense hardwoods are found. Symptoms, which can occur anywhere from a few days to weeks after being bitten by the infected mosquito, include fever, nausea, vomiting, and in more severe cases convulsions, tremors and even coma. Younger children are by far the most susceptible to severe disease and often suffer long-term neurological and cognitive difficulties. Because adults may have milder symptoms, many of these cases are not identified and go largely unreported.

“It’s odd to think of this seemingly exotic, yet little known mosquito-borne virus that primarily impacts kids being so potentially life altering. The long-term sequelae of La Crosse infection can contribute to poor academic performance, impaired physical functioning and behavioral problems. And it happens in these really rural counties of western North Carolina. Every time I talk about La Crosse, people – including many physicians – are surprised to learn this is happening essentially in our own backyard.”

But every summer, Brian Byrd, PhD, an environmental health professor at Western Carolina University does think about it, and so do his students, in an active undergraduate research program that has shown the virus is a persistent threat to North Carolina.

Tracking the Eastern Treehole Mosquito

When a child gets sick, Byrd gets a call from the health department or hospital. He goes to the family’s house to look for evidence of the treehole mosquito, using molecular tools to identify them. He also tries to address any problems he sees, like containers with rain water, or anything that can hold water.

“We’re working under the hypothesis that the risk may persist at house, because what we’ve found through our epidemiology records with the State and CDC, is that in some cases, kids are getting sick at the same time and going to the hospital the same week,” Byrd said. “At other times, a kid gets sick and then three years later, a sibling gets sick, while living at the same house.”

“There’s also evidence to suggest the risk may persist from year-to-year. For example, a child is sick and the family moves away. Then, a new family moves in and another child gets sick at the same house. We think this is linked to the biology of this virus, because the virus is passed from mosquito to the next generation of mosquito in the eggs.”

Boyce met Byrd through the Vector-Borne Disease Epidemiology, Ecology, and Response Hub (VEER), a multi-disciplinary research collaboration that Boyce established to study tick- and mosquito-borne diseases endemic to North Carolina.

Last year, the two formed a novel collaboration, funded by the N. C. Collaboratory, which will lay the foundation for an effective patient care and prevention effort.

Funded By the State, For the State

Jeffrey Warren, PhD, executive director of the N.C. Collaboratory says Boyce piqued interest when he showed that North Carolina, predominantly the Appalachian region, is one of the largest hotspots in the nation for the mosquito-borne virus.

“When Dr. Boyce suggested a joint partnership with Western Carolina University, we immediately knew this was an issue worth funding, in service to the people of our State,” Warren said.

Now just months into the three-year pilot project, the team is working with the CDC to collect and test collected mosquito samples that will advance the development and validation of new diagnostic tools. At the state level, they’re working with the N.C. Communicable Disease Branch at the Division of Public Health, to identify and record La Crosse cases, while at the same time building out a cohort of patients enrolled through a new partnership with the Department of Pediatrics at Mission Hospital to better characterize the clinical illness and identify best practices. Together Byrd and Boyce hope this effort will lead to improved prevention and control programs that can be adopted by local health departments, clinics, and hospitals.

“I think we do a good job with the vector side of it, and to some degree, the epidemiology, but one of our challenges has been not having the infectious disease expertise in Western North Carolina that UNC has,” explained Byrd.

“In my experience, which is more than 15 years, it’s very rare for a family member to know about La Crosse before a child gets sick. We need to get a better handle on these environmental variables, and we need to make sure people know it’s a problem, because it’s not going away.”

Bailey Kavanagh concluded her podcast with news that her daughter, back at school, was recovering with lingering symptoms. She also added that local health officials would be visiting her property to learn more, to try and help prevent other children from contracting the virus.

Learn more about Dr. Byrd’s research: Watch here (approximate timestamp 6:00).

About the Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases

The Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases (IGHID) at the UNC School of Medicine is an engine for global health research and pan-university collaboration, transforming health in North Carolina and around the world. As the PI’s comprehensive partner, IGHID facilitates research excellence while providing opportunities for investigators to nurture emerging scientists through training and service, to achieve positive patient care outcomes and sustainable practice.

-Kim Morris, APR