By Mina Hosseinipour, MD, MPH

Officials announced the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Malawi on April 2, 2020. At UNC Project Malawi, we’d been working for a month to carefully review and prepare for the virus. We established COVID preventive procedures and clinical management guidelines and planning for staff and staff relatives. We enhanced our oxygen supply through concentrators and obtained more oxygen cylinders. We worked with Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH) to assist in training and preparations for the onslaught.

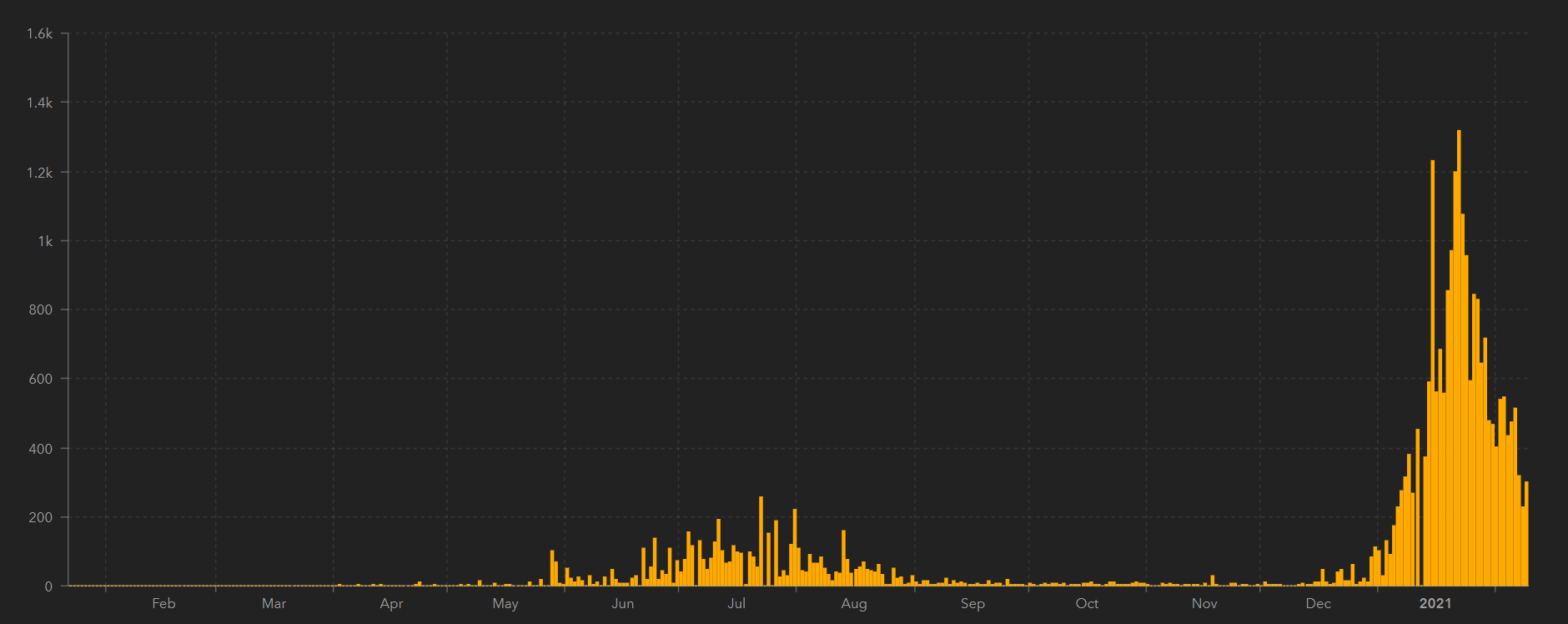

And then we waited for the cases to come. A series of events came and went, activities that should have prompted community spread of COVID-19 but didn’t. The month of June brought election campaigning and by early July, we saw a significant increase in cases in the country. The KCH COVID unit filled with patients. This wave lasted approximately two months and then, nearly as suddenly and without appreciable mitigation measures, the cases seemed to go away. Many of us wondered why the incidence of COVID fell so rapidly and nearly completely — we had no admissions, the COVID units closed, we saw less than 1 percent positivity rate among tested individuals, and seemingly no increased admissions, deaths or otherwise in the communities. Malawi was spared, it seemed, and the country seemed to rejoice. Through October and November, things seemed to be back to our usual existence.

In early December, we could see the epidemic picking up in South Africa and we knew there was constant traffic between our two countries. Countries throughout the region were seeing an uptick. Many of us recognized the threat and issued warnings to maintain vigilance, but with so few cases to point to, it was difficult to convey the potential seriousness to communities and our staff.

In mid-December, a visitor to one of the Project-Malawi research studies fell ill while conducting activities at the site. One week later, we learned the visitor eventually had tested positive and was admitted for treatment. By this time, one staff member was already symptomatic and had infected their family members and other household contacts. Our outbreak investigation eventually yielded four positive staff members and numerous staff requiring quarantine. As we recessed for the Christmas and New Year’s holidays, we alerted staff of this serious event and the need to practice COVID prevention measures over the holidays.

The timing of the reintroduction of the virus (and likely the new South African variant) could not have been worse. The holidays bring church services, family gatherings, weddings, and travel to home villages. The result was not just a second wave; it was more like a tsunami of COVID cases. Over the course of a week, the COVID units reopened and filled to capacity. At KCH, the medical short stay and its associated holding tent (now re-erected) overflowed with people spilling into hallways, corridors, and floor space. The demand for oxygen sky-rocketed. We struggle each day to maintain oxygen cylinders even after adding an oxygen plant at KCH in the summer after the first wave.

When KCH was over capacity, “the government decided to open a field hospital,” says Innocent Mofolo, our Project Malawi country director. “Bingu National Stadium, with a 200-300 bed capacity, has helped centralize and manage staff capacity as opposed to when we had several isolation centers around town. The government has replicated this field hospital model in other regions of Malawi. Management of critical disease continues to be a challenge, as our facilities do not have capacity to ventilate patients.”

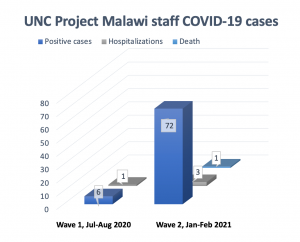

At Project Malawi, our preparations were more than adequate for the first wave, but we were rapidly stressed the second time around. When a staff member and a staff relative were admitted simultaneously, both requiring oxygen, we realized we could not maintain our oxygen cylinders to keep up with the rates of high-flow oxygen. We transitioned our cervical cancer C02 cylinders to carry oxygen, but the logistics remained challenging, particularly when the KCH oxygen plant broke and the entire country seemed to rely on getting cylinder refills in Blantyre, a four- to five-hour drive away. On the ground, entire research teams were absent from work from being cases, contacts, or caregivers. Announcements of staff losing parents or other relatives became commonplace, with many of these deaths confirmed to be COVID-related. We required a full-time clinical team to assess staff, we needed to establish a mental health counseling team, and we expanded our COVID team to conduct follow-up on staff. To date, with the second wave, 20 percent of our staff have been confirmed positive cases. Tragically, we lost Mr. George Bonomali, our human resources and administrative manager, to the virus.

At Project Malawi, our preparations were more than adequate for the first wave, but we were rapidly stressed the second time around. When a staff member and a staff relative were admitted simultaneously, both requiring oxygen, we realized we could not maintain our oxygen cylinders to keep up with the rates of high-flow oxygen. We transitioned our cervical cancer C02 cylinders to carry oxygen, but the logistics remained challenging, particularly when the KCH oxygen plant broke and the entire country seemed to rely on getting cylinder refills in Blantyre, a four- to five-hour drive away. On the ground, entire research teams were absent from work from being cases, contacts, or caregivers. Announcements of staff losing parents or other relatives became commonplace, with many of these deaths confirmed to be COVID-related. We required a full-time clinical team to assess staff, we needed to establish a mental health counseling team, and we expanded our COVID team to conduct follow-up on staff. To date, with the second wave, 20 percent of our staff have been confirmed positive cases. Tragically, we lost Mr. George Bonomali, our human resources and administrative manager, to the virus.

Will things get better for Malawi? We’re seeing new cases decreasing, and the hospital numbers seem to have plateaued despite rather modest adherence to mitigation and preventive measures. Having enough oxygen remains a challenge, but things have improved since the oxygen plant was repaired and organizations and citizens have donated cylinders and concentrators.

The Astra Zeneca vaccine is slated to be delivered here by the end of February with hopes we can begin to administer it in March. But new research suggests that this vaccine as well as the Johnson & Johnson and Novavax vaccines aren’t as effective at preventing mild to moderate disease against the South African variant. We hope, of course, that the vaccine will prevent severe disease and death. Our research site looks forward to being able to evaluate potential COVID-19 treatments through the ACTIV network, and we will be poised to engage with any new vaccine-related studies through the CoVPN network.

Mina Hosseinipour, MD, MPH, is a professor of medicine and scientific director for the Institute’s UNC Project-Malawi. UNC recently honored her with a 2021 Distinguished Teaching Award for Post-Baccalaureate Instruction.