Robert Flick is a student at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. He has completed both the Doris Duke International Clinical Research Fellowship and the UJMT Fogarty Global Health Fellowship. In this blog post, he shares how these fellowships allowed him to conduct operational research in Malawi and pay tribute to a friend and former colleague.

I used to avoid research. The word itself evoked images of beakers, pipettes and white coats – sterile places impossibly removed and irrelevant from the health inequities that drove me to pursue a career in medicine in the first place.

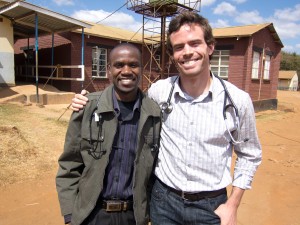

My friendship with Peter changed all of that. While we were roughly the same age, Peter grew up in a rural district of Malawi, a world apart from my childhood in a middle-class suburb outside Baltimore. We met soon after I first arrived in Malawi in 2011, and were both assigned to help support logistics in the most distant corners of Neno, a remote and rugged district.

It was hot, dusty, exhausting work. The days were long, and usually began with a predawn frenzy of loading pickup trucks and land rovers with supplies, followed by a morning spent rattling down rutted dirt roads. The health posts were often a single room under a tin roof, and by the time we arrived, the line would be several hundred patients long. The need was always overwhelming. The end of each day typically found us exhausted, covered in a film of sweat and dust.

Peter and I developed a strong friendship and I grew to depend on his unfailingly optimistic outlook in spite of the desperate straits we often found ourselves in. He was one of my first friends after arriving, and patiently helped me learn to navigate the culture and language of Malawi, a country I would grow to love.

It was while traveling outside of Malawi when I received the news that he had died. His clinical decline was swift and inexorable: massive ascites, drenching night sweats, a productive cough. His clinicians suspected tuberculosis, began empiric treatment and transferred him to a tertiary hospital in the nearest city. He died en route. While visiting his childhood home several months later, I was unable to offer even a firm diagnosis to his grieving mother.

I was outraged at our collective inability to save his life, and identified the systematic failure to equitably implement the fruits of modern medical science as a major contributor. It was through the lens of personal loss that I first began to understand the “implementation gap” of global health—the challenges of applying best practices gleaned from controlled studies to the gritty reality of places like Malawi. What systematic barriers prevented Peter from accessing high-quality screening, diagnostic and treatment services? I realized I had found my research niche, and channeled my outrage into operational research in Malawi.

Thanks to support from the Doris Duke International Clinical Research Fellowship and the UJMT Fogarty Global Health Fellowship, I was able to spend two consecutive years in Malawi cultivating this passion under the mentorship of Dr. Mina Hosseinipour and other experienced researchers. My research focused on strategies to improve routine tuberculosis screening, specifically through the use of community health workers. Through operational research, we were able to address import health inequities, describe critical gaps in the current health infrastructure and share our lessons with the global community.

The support of these fellowships proved invaluable in shaping my career for several reasons. Most importantly, it provided the opportunity to immerse myself in Malawi for two consecutive years. This allowed me to develop meaningful personal and professional relationships, to learn from my Malawian friends and colleagues, and to begin grasping the intangible lessons that are critical to pursuing research in this unique setting. Further, hands-on experience under the mentorship of experienced faculty members at UNC Chapel Hill provided critical lessons on all steps of the research process, from proposal writing, to quantitative analysis, to manuscript preparation. Together, these fellowships helped to both cultivate my understanding of how to conduct meaningful research, and helped me lay the groundwork for my own research career.

I used to avoid research. But the loss of Peter showed me my definition of the profession had been too narrow. Improving health care delivery can happen in the lab, but also in the field. As I return to medical school, I encourage other students to be open to the call to a research career and to consider applying for a fellowship to explore these opportunities to improve global health.